Travis declares a time to stand

By Scott Huddleston, San Antonio Express News

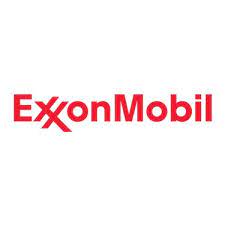

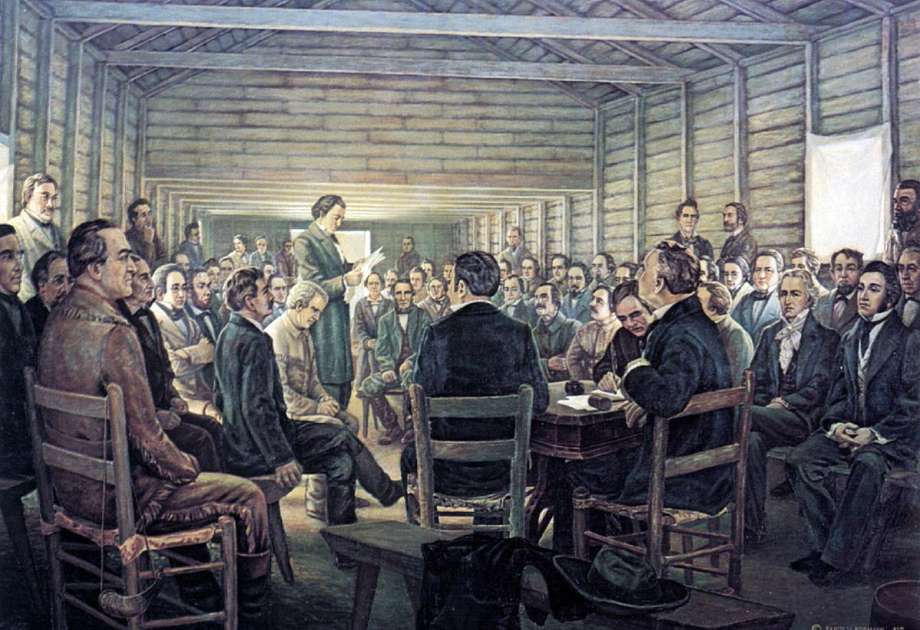

“The Reading of the Texas Declaration of Independence,” by Charles and Fanny Normann, is displayed at the Star of the Republic Museum at the Washington on the Brazos State Historic Site.

The last batch of letters Alamo commander William Barret Travis is known to have sent out of the battle compound during the 1836 siege included two to delegates gathering to declare Texas independence and an admonishment to his son’s guardian to “take care of my little boy.”

“The spirits of my men are still high, although they have had much to depress them,” Travis wrote on March 3 in an official report to the convention 100 miles to the east at Washington on the Brazos.

He reported having 20 days worth of provisions and requested 500 pounds of cannon powder, 200 rounds of cannon balls, 10 kegs of rifle powder and some lead.

“The power of Santa Anna is to be met here or in the colonies; we had better meet them here, than to suffer a war of desolation to rage our settlements,” he wrote.

More recognized in popular historical narratives is a much shorter letter, less than half as long as his official dispatch, that Travis wrote to convention delegate Jesse Grimes, one of four representatives of the Washington municipality at the convention. Books about the Alamo have described Grimes as a “friend” or “good friend” of Travis, although little has been written about their relationship.

“Let the convention go on and make a declaration of independence, and we will then understand, and the world will understand, what we are fighting for,” Travis wrote in an oft-quoted excerpt from the letter to Grimes.

In his book, “A Time To Stand,” Walter Lord said Travis expressed to Grimes “much more eloquently than in his official correspondence” why he was making a stand — for reasons that transcended strategy, bonds among men in the garrison and the desire to defend their homes.

“More than all these … he felt the spirit of the times — the conviction that liberty, freedom and independence were in themselves worth fighting for; the belief that a man should be willing to make any sacrifice to hold these prizes,” Lord wrote.

In the Grimes letter, Travis wrote, “If independence is not declared, I shall lay down my arms, and so will the men under my command.”

“But under the flag of independence, we are ready to peril our lives a hundred times a day, and to drive away the monster who is fighting us under a blood-red flag, threatening to murder all prisoners and make Texas a waste desert,” he added.

William C. Davis, in “Three Roads to the Alamo,” a biography of Travis and Alamo defenders James Bowie and David Crockett, notes that the passage included “the only comment about surrender” that Travis made during the siege.

“It was only for effect, for he knew by now that surrender was out of the question,” Davis wrote.

In “Texian Iliad,” about the Texas Revolution, Stephen L. Hardin noted that Travis revealed “more of his true feelings” to Grimes, “his close friend.” Although the 59 signers of the declaration would risk their lives by putting their names to paper, Travis wanted Grimes to know about 200 Alamo defenders were prepared to die for the cause.

According to Davis, Travis handed the letters to John W. Smith, believed to be the last messenger from the Alamo, called “El Colorado” by Tejanos because of his red hair. He also gave Smith two other personal messages, including one to David Ayres, a merchant and Methodist missionary who ran a school at home with his wife. Travis had left his son, Charles, who was about 7, to live with Ayres and attend the school.

“Take care of my little boy,” Travis pleaded. “If the country should be saved, I may make for him a splendid fortune; but if the country be lost and I should perish, he will have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country.”

The recently divorced Travis also may have sent a personal note to his fiancee, Rebecca Cummings, who lived near San Felipe in East Texas. According to Davis, an account by Texas author Mary Austin Holley, documented in papers at the University of Texas, indicates Cummings received a message carried by the Alamo’s last courier. Travis had begun his letter to Grimes with, “Do me the favor to send the enclosed to its proper destination instantly.” That is presumed to be the note to Cummings.

Davis reported that others “heard Rebecca screaming” when she was told Travis and the other Alamo defenders had died. Contents of the note from Travis to Cummings would be “forever an eternal secret between them,” Davis added.

Another mystery is the relationship between Travis, 26, born in South Carolina, and 48-year-old Grimes, a North Carolina native. The two had lived in neighboring Alabama counties before coming to Texas — Grimes in 1826, Travis in 1831.

Based on family papers and other documents at UT, longtime history researcher Robin Webb-Lucas said they both served on government councils in San Felipe.

“Grimes was a regidor on the subcommittee for safety, and was the district treasurer of the Viesca District of San Felipe,” said Webb-Lucas, who has lineal ties to Texas Revolution. “Travis was elected the secretary to the ayuntamiento (city council) of San Felipe in 1834.”

The original letter between the two has never been found. But it was printed in the March 24, 1836, edition of the Telegraph and Texas Register. Grimes went on to represent Washington County, then later Montgomery County, in the Congress of the Republic of Texas, and served as a legislator after U.S. statehood began in 1845. He died in 1866 and is buried at the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. Grimes County is named for him.

The Star of the Republic Museum, Barrington Living History Farm and Independence Hall, a replica of the building where delegates met in 1836, are on the grounds of Washington on the Brazos State Historic Site. A free Texas Independence Day celebration is set for March 3-4 at the 293-acre park, with live music, food, traditional crafts and simulated cannon and musket fire.

Museum director Houston McGaugh said letters Travis received at the Alamo from officials in East Texas may have been burned, to keep them from being gleaned for intelligence, or could have been seized, and now stored in archives somewhere in Mexico.

“That would be an interesting trove of letters to find,” McGaugh said.

shuddleston@express-news.net | Twitter: @shuddlestonSA